George’s solution was straightforward; eliminate taxation on buildings in favor of a tax on the value of land. Land in central cities would be valued highly due to extensive infrastructure and high potential for profitability, while rural land would be assessed and taxed at a much lower level.[14] George argued this to be the only tax that did not “over-burden or discourage production,” was, “easy and cheap to collect,” was restricted from evasion and fell upon citizens equitably.[15] The land value tax would make impossible the profit-snatching game of land speculation, and encourage economic growth by spurring productive and efficient use of land for long term capitalist gains. By releasing land previously held by speculators to those who will actually use it, George believed employment would be created and poverty diminished[16]. This tax further addresses the problems states ran into with property tax: land value is more easily assessed than buildings and personal property, and virtually impossible for holders to conceal — as some contemporary proponents have pointed out, land owners “can’t stash it in a secret Panamanian bank account.”[17]

The problems faced with property tax by the federal and state governments throughout American history have been almost entirely due to the more specific taxation on buildings and intangible property partnered with the curious void of taxation on land. Hidden beneath this has been the possibility of a tax that boosts economies while simultaneously generating higher revenues. By taxing a communally created value (land), governments earn revenue based on the betterment of their counties, cities, and neighborhoods.[18] This betterment leads to higher land values and thus higher revenues that can then be reinvested in the community, leading again to higher revenues. In this way, land value tax triggers a self-perpetuating chain reaction of economic growth. Land value taxation allows a community to reap the benefits of its own labor. While sales taxes are regressive and income taxes arguably discourage work due to the structure of tax brackets, the land value tax is equitable, non-distortionary, and inelastic[19].

Sprawl

Kunstler translates George’s economic problem into the framework of an urban ecosystem:

"Our system of property taxes punishes anyone who puts up a decent building made of durable materials. It rewards those who let existing buildings go to hell. It favors speculators who sit on vacant or underutilized land in the hearts of our cities and towns. In doing so it creates an artificial scarcity of land on the free market, which drives up the price of land in general, and encourages ever more scattered development, i.e., suburban sprawl."[20]

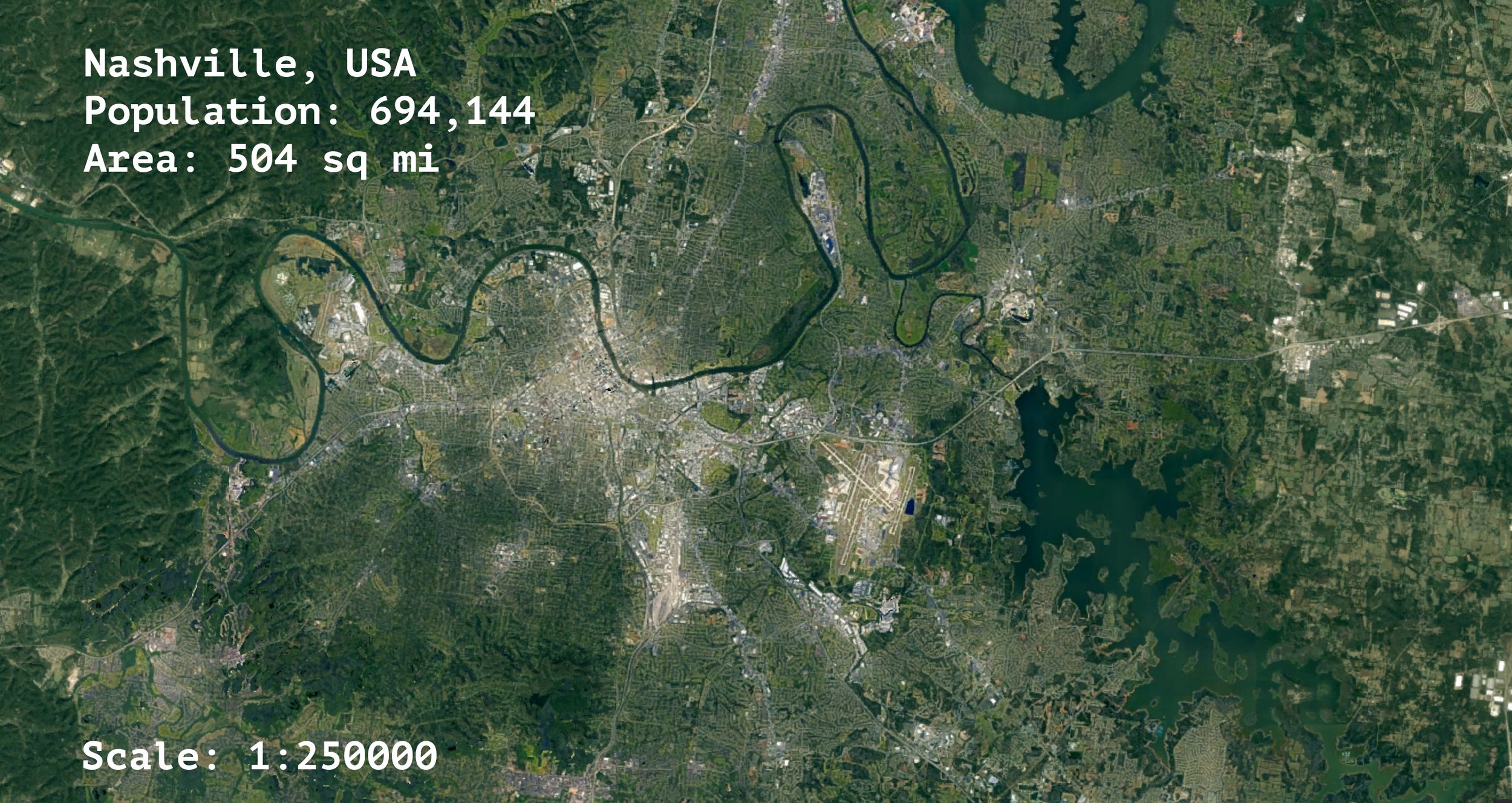

The intangible realm of economics has a startling correlation with the most concretely physical aspects of society: our built environments. Land speculation punches unsightly holes in the urban fabric of cities and flings development further outward. The very existence of cities supports agglomeration theory–that there is economic advantage in closeness. So why does Phoenix (among other US cities) look like it was built to keep everyone and everything as far apart as possible?

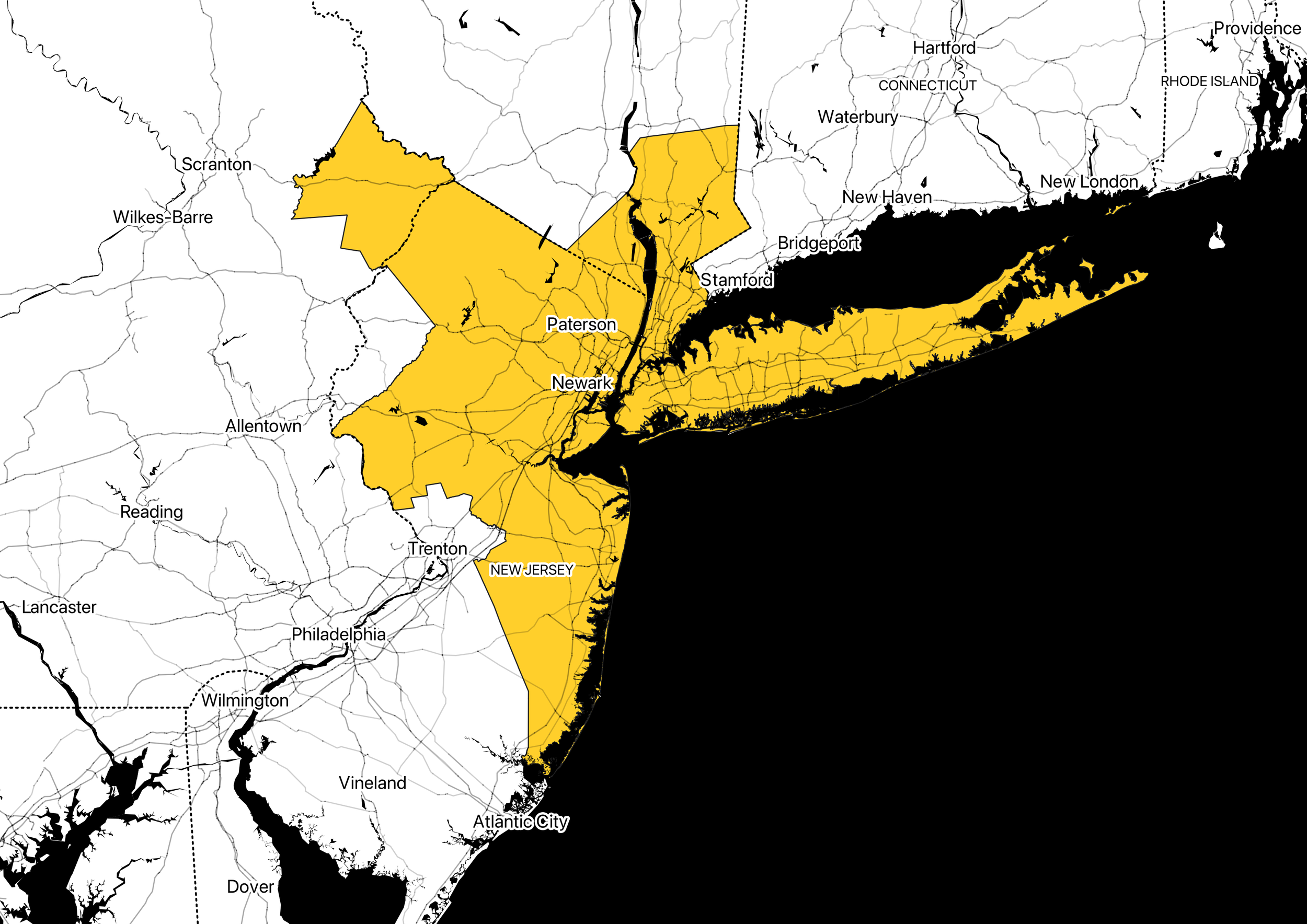

Henry George did not live to witness the epidemic of sprawl in America, but due to it his theories are more relevant than ever. Mary Rawson of the Urban Land Institute asserts that, “The sprawl problem is almost purely the result of land speculation at work,” and that land value taxation would create, “pressures tending toward the efficiency of development” by taxing land speculators based on the potential earning power of their property.[21] This relationship is partially due to the physical barrier to density posed by vacant lots, but perhaps even more so by the high land prices speculators create. By restricting so much land from the open market, speculators create an artificial scarcity of land that drives up surrounding prices and pushes development further out in effort to find affordable land.[22]

Residential density is heavily discouraged under current property tax structure. High density makes communities walkable, public transportation effective, and automobile use optional.[23] It is important to note that the land value tax not only spurs development, but more specifically that it spurs dense development. In theory, it would cause sprawl to contract by incentivizing development in the most dense urban areas and disincentivizing development on the exurban fringe. Urban planners and city politicians struggling to combat sprawl tend to jump to coercive measures with mixed results (Portland, Oregon’s urban growth boundary is among the more successful examples, but even Portland struggles to combat sprawl within the boundary)[24].

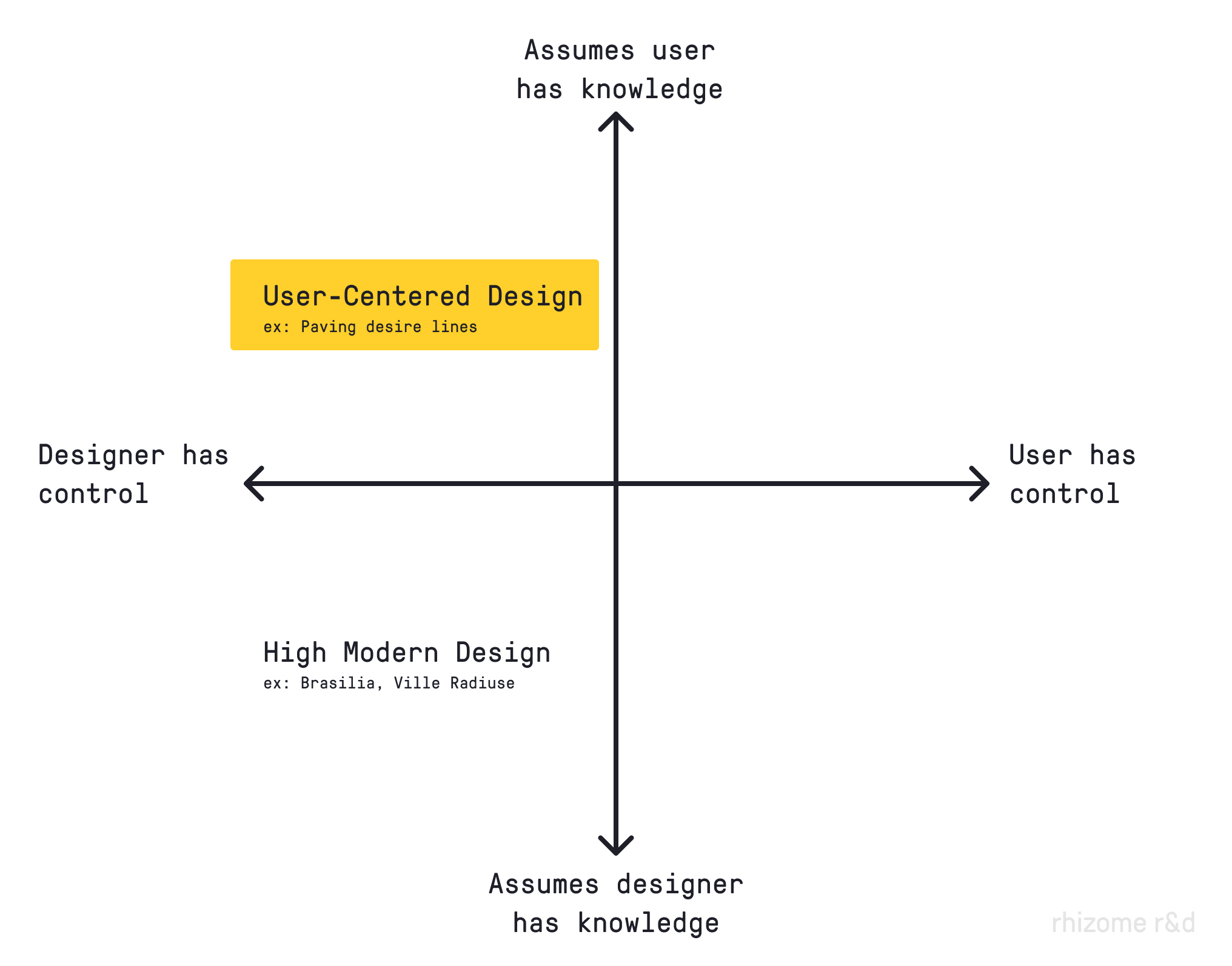

Considering the incentive to sprawl due to property tax structure, these measures are akin to herding cats in an aviary as opposed to placing a bowl of catnip in the center. This approach ignores the artificially constructed enticements to sprawl, the fundamental root of the problem. The field of urban planning and governance often attempts to combat behavior with restrictions as opposed to merely eliminating distortions in tax structure to incentivize positive behavior – in this case, compact development.

Vacancy

Cities like Detroit, New Orleans, and St. Louis have been caught in a vicious cycle. The loss of industry has led to economic decline, which results in vacancy, which leads to reduced public funds, high crime, and less investment, all of which leads to further economic decline. High vacancy rates are the both the physical result of economic decline as well as a primary cause of economic decline. In many cities, especially in the rust belt, landowners may not be incentivized to speculate within a booming market but the cost of holding land vacant remains negligible.

Meanwhile many of these cities have increased property taxes as much as possible in attempt to maintain the public budget in the face of population loss.[25] The highest local tax rates in the country tend to belong to shrinking cities in and around the rust belt: Detroit, Milwaukee, Columbus, and Baltimore all fall within the top ten most taxed cities in the nation.[26] These cities rely most heavily on property tax. In other words, the cost of building has increased, further disincentivizing development in the places that need it most.

A revenue-neutral shift from taxes on buildings to taxes on land would put the highest development pressures on the vacant parcels (and surface parking lots) in the urban cores of these cities.

Inequality

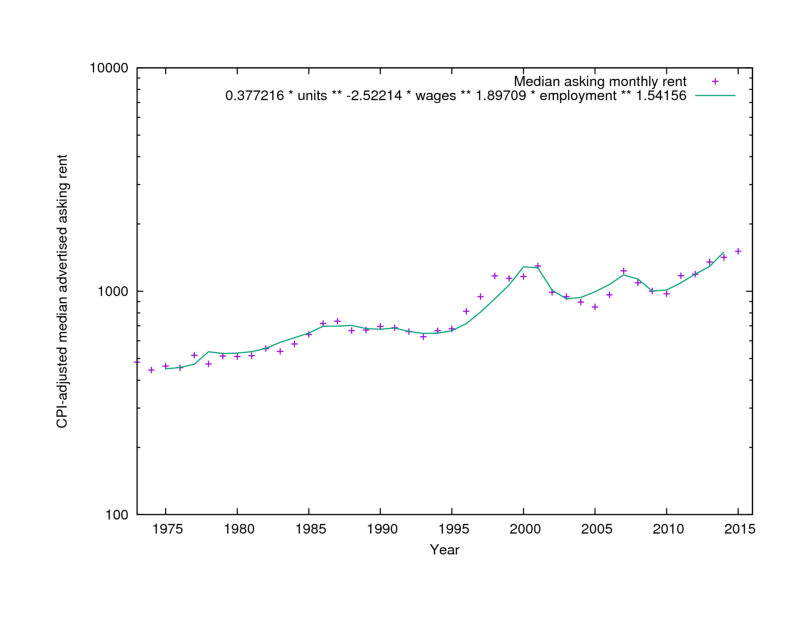

Wealth inequality is perhaps the primary driver of land value tax considerations today, especially given the dramatic affordable housing crisis happening in wealthy coastal cities. Proponents of land value tax argue that shifting tax weight from buildings to land will significantly lower the price of land and housing.[27] By this logic, land value tax would spur owners of under-developed land to either (A) build housing in order to cover their increased holding costs or (B) sell their land to someone who will. Together, these actions would increase the supply of both housing and land, thereby reducing the price of housing and the acquisition cost of land. This could have considerable effects on the supply of affordable housing in dense urban areas, but it also redistributes wealth disparities.

As Amit Ghosh, former San Francisco Chief of Comprehensive Planning, points out, the lowering of development costs via land value taxation opens the door to sizable expansions in inclusionary housing policies. San Francisco’s current affordable housing requirements of 12% to 20% (depending on if the housing is provided on or off-site) could be plausibly increased to as much as 60% with dramatically lower land prices.[28]

Matthew Rognlie of MIT recently identified that housing capital explains nearly all capital value growth in the United States over the last 50 years. More specifically, the increasing value has been in the location of housing—in other words, in land value.[29] This finding suggests that the un-taxed value of land is the primary driver of growing wealth inequality.

Central to the theory of land value taxation is a basic principle of fairness. If a property owner in San Francisco lucked out in buying prior to the recent real estate boom, the value of their property assets have increased dramatically despite no productive action on the property owner’s part. This value gain is an unearned increment, and deeply exacerbates the stratification of wealth in the city. A tax on land (the logistical hurdles of California’s Prop 13 notwithstanding) could correct this imbalance.

Pennsylvania: A Case Study

Despite its occasional proposal in the realm of economic discourse and policy analysis for urban sustainability, the land value tax has yet to be fully implemented in any American city. The solution was briefly posed for increasing energy consumption by the House Committee on Banking, Finance, and Urban Affairs of the 96th Congress in the early 1980’s, but received little further attention.[30] In search of concrete evidence to uphold the theories of land value tax proponents, there are a handful of case studies to be made. The closest model of land value tax implementation in the US today is the split-rate style property tax imposed in a number of Pennsylvania cities and townships, the most notable being Pittsburgh and Harrisburg. As of 1996, the land-to-building tax ratio for Pittsburgh and Harrisburg was 5.61:1 and 4:1, respectively[31]. Following Pittsburgh’s implementation of the split-rate tax in the late 1970’s, building permits issued in the city increased 293% over the national average[32]. When comparing the change in average annual value of building permits between the 1960’s and 1980’s, the value of Pittsburgh’s building permits far exceeded those of similarly sized cities in the region. The average building permit in the cities studied by the University of Maryland in 1992 (all of which possessed a single-rate property tax structure) lost about 29.9% of its value over this period. In contrast, Pittsburgh’s average building permit increased by 70.4% in value.[33] Harrisburg, which began its split-rate property tax in the mid 70’s, saw the number of vacant structures within the city plummet from 4,200 in 1982 to less than 500 by the late 90’s.[34] The mayor of Harrisburg attributed much of the city’s economic strength in that period to its innovative property tax solutions.[35]

Despite the cascade of well-documented success, Pittsburgh removed its split-rate property tax system in 2000 following public disapproval due to higher reassessed values causing taxes to increase. Though this is actually a positive indicator of the split-tax rate’s achievement, the true irony of the situation was revealed in the aftermath; most homeowners and business owners ultimately paid higher taxes following the rescission[36]. Construction spending during the two years following rescission was 21% lower than during the two years prior, even while average construction activity for the nation increased.[37] It is difficult to determine the exact degree of impact the split-rate tax system had on these variables in Pittsburgh, but most factors suggest a strong relationship between the ratio of land to building tax and the rate of compact development. International examples of land value taxation exist in South Africa, Denmark, New Zealand, and Australia, all of whom have experienced varying degrees of similar results.[38]

Land Value Tax in Political Context

The mainstream dialogue over taxation has hinged primarily on a one dimensional spectrum: Should taxes be lower or higher? While pundits and politicians holler from their respective corners, the fundamental question over the point of taxation finds little room on the table. Some argue that the point of taxation does not matter, as money is taken from the economy at large regardless. Henry George counters this assault, writing that, “The mode of taxation is, in fact, quite as important as the amount. As a small burden badly placed may distress a horse that could carry with ease a much larger one properly adjusted, so a people may be impoverished and their power of producing wealth destroyed by taxation, which, if levied in another way, could be borne with ease.”[39]

It could be argued that the land value tax transcends the ideological polarity of our time; it fits neatly into the intellectual framework of both major political parties without giving in to either party’s tendency towards higher or lower taxes. The theoretical grounds of the land value tax have been supported right-leaning organizations,[40] while its results have been heralded by those on the left pushing for progressive policies. In his day, George was labeled both a libertarian and a socialist, though both characterizations failed to grasp the core pragmatism of his proposal.[41] Given the acceptance found across the political spectrum and the potential economic growth induced by a revenue-neutral shift, the lack of consideration at the municipal or even federal level can only be explained by the entrenched power of large landowners.

Due to the 1865 court decision of Clark v. City of Des Moines, most municipal governments are restricted from property tax reforms unless consented by their superior state government (this ruling would later be known as “Dillon’s Rule”).[42] In Pennsylvania, reform came about purely under the permission of the state. The state legislature authorized Pittsburgh and Scranton to redesign tax structure in 1913, and numerous smaller cities in 1951.[43] As a number cities are learning as they push towards property tax reform, municipal changes of this magnitude require pressure at the state level. Clearly this creates an administrative tension: if a revenue source is administered, collected, and utilized entirely at the local level, should the right to alter corresponding legislation be held at the state level? This dilemma can be applied to a myriad of issues, but given the degree at which local governments rest on property tax it is a fundamental question in this arena.

State constitutions and statutes would generally require amendment to allow for land value taxation. Initial roadblocks include common clauses commanding taxes be applied identically to all taxpayers – a provision potentially at odds with land value taxation due to the possibility of two parcels with the same overall value but different land values.[44] Amendment solutions range from differential classification under tax law for land and buildings to the total exemption of improvements from taxation. Though logistical concerns have been raised in the past, the technological development of assessment methods has improved greatly due to geographic information systems and computer-assisted mass appraisal.[45] The precision of assessment necessitated by land value taxation can now be conducted in an efficient and effective manner, but political obstruction remains.

Should reforms be reached at the state level (perhaps as an assisting tool to ailing local economies and state budget shortfalls), a more widespread analysis of effectual change could lead to policy review at the federal level. As has occurred on numerous occasions in American history, experimentation at the state level can lead quickly to national reform. The artificial devaluing of land may be a contributing determinant to the violence of economic swings — should the land value tax reach the national stage’s discourse, it could very well receive swift implementation.

Conclusion

Far from the headlines of news cables and beneath the layers of public policy discourse rests a pragmatic strategy that could potentially overhaul the fundamentals of local economies towards efficiency, stability, and sustainable productivity. While it rarely sees the daylight of discussion in town hall meetings or congressional hearings, the ramifications of land value taxation have been analyzed and dissected for over a century. The problems potentially solved are vast, but all stem from a single root — land has become a devalued commodity.

Should land be reassigned its value by our economic systems, it follows naturally that market incentives should ignite a swing towards geo-efficient and socially-just development. In cities with excessive sprawl, the land value tax should be considered as a component in the strategy to curb greenfield development. In cities with high vacancy and weak economies, the land value tax should be considered as a component in the strategy to encourage urban infill and incite economic activity. In the booming but vastly inequitable economies of large coastal cities, the land value tax should be considered as a strategy for providing more affordable housing and correcting the imbalance of severe wealth inequality. The question then, is which major city is willing to experiment first?

Footnotes

[1] Stevens, Elizabeth Lesly. 2011. “A Tax Policy With San Francisco Roots.” The New York Times, July 30. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/31/us/31bcstevens.html.

[2] Glenn Fisher, The Worst Tax?: A History of The Property Tax in America (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1996), 7.

[3] Glenn Fisher, "Some lessons from the history of the property tax. (Cover story)." Assessment Journal 4, no. 3 (May 1997): 40.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Fisher, The Worst Tax?: A History of The Property Tax in America, 207.

[7] Ibid., 4.

[8] Fisher, "Some lessons from the history of the property tax. (Cover story)," 40.

[9] James Howard Kunstler, Home From Nowhere (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 197.

[10] Ibid., 198.

[11] Fisher, "Some lessons from the history of the property tax. (Cover story)," 40.

[12] Mark Blaug, "Henry George: rebel with a cause." European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 7, no. 2 (Summer2000 2000): 270-288.

[13] Henry George, "Everybody Works But The Vacant Lot," NYPL Digital Gallery, http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?1160280

[14] Kunstler, Home From Nowhere, 201.

[15] Barbara Goodwin, "Taxation in Utopia." Utopian Studies 19, no. 2 (June 2008): 315.

[16] Aaron M Sakolski, Land Tenure and Land Taxation in America (New York: Robert Shalkenbach Foundation, Inc., 1957), 276.

[17] Kunstler, Home From Nowhere, 202.

[18] Ibid., 197.

[19] Joseph H Haslag, How to Replace the Earnings Tax in St. Louis, Policy Study 5, http://showmeinstitute.org/docLib/20070411_smi_study_5.pdf

[20] Kunstler, Home From Nowhere, 196-197.

[21] Urban Land Institute, Property Taxation and Urban Development, ed. Mary Rawson, Research Monograph 4 (Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute, 1961), 26-27.

[22] Ibid., 28.

[23] Center for Neighborhood Technology, Pennywise, Pound Fuelish: New Measure of Housing and Transportation Affordability, 8.

[24] Metro Regional Government, Metro, http://www.metro-region.org/

[25] Margolis, Jason. 2015. “On The Road To Recovery, Detroit’s Property Taxes Aren’t Helping.” NPR.org. http://www.npr.org/2015/05/27/410019293/on-the-road-to-recovery-detroit-property-taxes-arent-helping.

[26] “Top 10 Cities with the Highest Tax Rates.” 2015. USA TODAY. http://www.usatoday.com/story/money/personalfinance/2014/02/16/top-10-cities-with-highest-tax-rates/5513981/.

[27] Kunstler, Home From Nowhere, 200.

[28] Ghosh, Amit. "Understanding Land Value." Lecture, UC Berkeley Department of City and Regional Planning, Berkeley, CA, November 16, 2015.

[29] Rognlie, Matthew. "A note on Piketty and diminishing returns to capital." Tillgänglig:< http://www. mit. edu/~ mrognlie/piketty_diminishing_returns. pdf (2014).

[30] House Committee on Banking, Finance, and Urban Affairs, Subcommittee of the City. Compact Cities: Energy Saving Strategies for the Eighties. Report. 96th Congress, 2nd Session. 1980. 8 p. Committee Print 96-15.

[31] Wallace Oates and Robert Schwab, "The Impact of Urban Land Taxes: The Pittsburgh Experience," National Tax Journal L1 (March 1997): 2.

[32] Kunstler, Home From Nowhere, 204-205.

[33] Wallace Oates, Robert Schwab, and Universty of Maryland, Urban Land Taxation for the Economic Rejuvenation of Center Cities: The Pittsburgh Experience (Columbia, MD: Center for the Study of Economics, 1992).

[34] Alanna Hartzok, "Pennsylvania's Success With Local Property Tax Reform: The Split Rate Tax." American Journal of Economics & Sociology 56, no. 2 (April 1997): 205-213.

[35] Edward J. Dodson, “Saving Communities: It Matters How Government Raises Its Revenue” (powerpoint presentation, March 2010) 27.

[36] Ibid., 21.

[37] Ibid., 22.

[38] Richard F Dye, Richard W England, and Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Assessing the Theory and Practice of Land Value Taxation, Policy Focus Report, 16,

https://www.lincolninst.edu/pubs/dl/1760_983_Assessing%20the%20Theory%20and%20Practice%20of%20Land%20Value%20Taxation.pdf

[39] Henry George, Progress and Poverty (1879; New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, 1981), 409.

[40] Haslag, How to Replace the Earnings Tax in St. Louis, Policy Study 5.

[41] Goodwin, “Taxation in Utopia”, 315.

[42] Jesse J Richardson, Meghan Zimmerman Gough, and Robert Puentes, Is Home Rule The Answer?: Clarifying the Influence of Dillon's Rule on Growth Management , 8, http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/rc/reports/2003/01metropolitanpolicy_jesse%20j%20%20richardson%20%20jr/dillonsrule.pdf

[43] Dye, England, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Assessing the Theory and Practice of Land Value Taxation, 13.

[44] Ibid., 24.

[45] Ibid., 25.

References

Beck, Hanno T. "Land Value Taxation and Ecological Tax Reform." Land-Value Taxation: The Equitable and Efficient Source of Public Finance (1999). http://www.taxpolicy.com/etrbeck.htm#notes

Blaug, Mark. "Henry George: rebel with a cause." European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 7, no. 2 (Summer 2000): 270-288.

Center for Neighborhood Technology. Pennywise, Pound Fuelish: New Measure of Housing and Transportation Affordability. http://www.cnt.org/repository/pwpf.pdf

Dodson, Edward J. “Saving Communities: It Matters How Government Raises Its Revenue.” Presentation, March 2010. http://www.authorstream.com/Presentation/ejdodson-349627-saving-communities-narrated-march-2010-taxation-economic-development-business-finance-ppt-powerpoint/

Dye, Richard F, Richard W England, and Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Assessing the Theory and Practice of Land Value Taxation. Policy Focus Report. https://www.lincolninst.edu/pubs/dl/1760_983_Assessing%20the%20Theory%20and%20Practice%20of%20Land%20Value%20Taxation.pdf

Fisher, Glenn W. "Some lessons from the history of the property tax. (Cover story)." Assessment Journal 4, no. 3 (May 1997): 40.

Fisher, Glenn. The Worst Tax?: A History of The Property Tax in America. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1996.

George, Henry. "Everybody Works But The Vacant Lot." NYPL Digital Gallery. http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?1160280

George, Henry. Progress and Poverty. 1879; New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation,

Ghosh, Amit. "Understanding Land Value." Lecture, UC Berkeley Department of City and Regional Planning, Berkeley, CA, November 16, 2015.

Goodwin, Barbara. "Taxation in Utopia." Utopian Studies 19, no. 2 (June 2008): 313- 331.

Hartzok, Alanna. "Pennsylvania's Success With Local Property Tax Reform: The Split Rate Tax." American Journal of Economics & Sociology 56, no. 2 (April 1997): 205-213.

Haslag, Joseph H. How to Replace the Earnings Tax in St. Louis. Policy Study 5. http://showmeinstitute.org/docLib/20070411_smi_study_5.pdf

Kenworthy, J R, and F B Laube. ) An International Sourcebook of Automobile Dependence in Cities, 1960-1990. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1999.

Kunstler, James Howard. Home From Nowhere. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

Longman, Phillip J. "Who Pays For Sprawl?" US News and World Report, April 19, 1998. http://www.usnews.com/usnews/news/articles/980427/archive_003780.htm

Margolis, Jason. 2015. “On The Road To Recovery, Detroit’s Property Taxes Aren’t Helping.” NPR.org. http://www.npr.org/2015/05/27/410019293/on-the-road-to-recovery-detroit-property-taxes-arent-helping.

Metro Regional Government. Metro. http://www.metro-region.org/

Oates, Wallace, and Robert Schwab. "The Impact of Urban Land Taxes: The Pittsburgh Experience." National Tax Journal L1 (March 1997): 2.

Oates, Wallace, Robert Schwab, University of Maryland. Urban Land Taxation for the Economic Rejuvenation of Center Cities: The Pittsburgh Experience. Columbia, MD: Center for the Study of Economics, 1992.

Richardson, Jesse J, Meghan Zimmerman Gough, and Robert Puentes. Is Home Rule The Answer?: Clarifying the Influence of Dillon's Rule on Growth Management. http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/rc/reports/2003/01metropolitanpolicy_jesse%20j%20%20richardson%20%20jr/dillonsrule.pdf

Sakolski, Aaron M. Land Tenure and Land Taxation in America. New York: Robert Shalkenbach Foundation, Inc., 1957.

Sierra Club. Sprawl Costs Us All: How Your Taxes Fuel Suburban Sprawl. Edited by Nicholas L. Cain, 2000. http://www.sierraclub.org/sprawl/report00/sprawl.pdf

Stevens, Elizabeth Lesly. 2011. “A Tax Policy With San Francisco Roots.” The New York Times, July 30. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/31/us/31bcstevens.html.

“Top 10 Cities with the Highest Tax Rates.” 2015. USA TODAY. http://www.usatoday.com/story/money/personalfinance/2014/02/16/top-10-cities-with-highest-tax-rates/5513981/.

Urban Land Institute. Property Taxation and Urban Development. Edited by Mary Rawson. Research Monograph 4. Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute, 1961.

Williams, Karl. "Land Value Taxation: The Overlooked but Vital Eco-Tax." Cooperative Individualism. http://www.cooperativeindividualism.org/williams_lvt_overlooked_ecotax.html

Zhao, Zhenxiang, and Robert Kaestner. "Effects of urban sprawl on obesity." Journal of Health Economics 29, no. 6 (December 2010): 779-787.