The User Experience of American Democracy

I have an admission to make: I can’t keep up with politics.

Sure, I have a general sense of what is going on, but the sheer scale and complexity of it all is utterly unapproachable. The last voter guide I received in the mail was over 200 pages long. I feel overwhelmed, and I have a degree in political science! To truly process in our information-soaked era demands not only constant attention to an avalanche of biased news, but a broad and deep understanding of policy implications and a supernatural ability to distinguish signal from noise in the chaos.

Plenty have been turned off to politics entirely. Only 37% of Americans could name their representative in a recent poll, while three-fourths of young adults couldn’t name a senator from their home state. Only 55% of voting-age Americans voted in the 2016 election. The popular media narrative blames our political apathy for allowing the politics of our government to move so far from the politics of the people it governs. Conventional wisdom says Americans just don’t care.

In user experience (UX) design this narrative is called “blaming the user” and it is the surest way to fail as a designer. The story of the apathetic voter is a well-worn trope, but what if Americans are simply alienated by bad design? When Thomas Jefferson argued that democracy requires well-informed citizens he probably feared a dearth of public information, but what happens when voters face information overload?

“…wherever the people are well-informed they can be trusted with their own government.” — Thomas Jefferson

Consider the number of political offices that the well-informed citizen is expected to follow. Thanks to the gargantuan size of the United States and the federalist system intended to connect people with government, Americans must keep tabs on a daunting array of offices. Each office is governed by a unique set of rules and endowed with a unique set of powers. Most of us are represented by a city council member, a state house representative, a state senator, a U.S. representative in the house, and two U.S. senators. That’s just the legislative branches. In the executive branches, voters must generally choose a mayor, a county executive, a state attorney general, a treasurer, a secretary of state, a governor, a lieutenant governor, and the president of the United States. If you’re counting, that’s roughly 14 offices with plenty more in judgeships, public defenders, transit boards, and local school systems.

By comparison the citizens of Denmark — a country where voter turnout regularly surpasses 85% — vote for about 5 offices (if you include their vote in the European Union).

The electoral college map if “Did not vote” had been a candidate in the 2016 election. Source

Still, the well-informed citizen needs to know more — each of those races may have candidates from two or more parties. In the 2018 election, there were over 12,400 candidates on ballots across the country. It may appear that our two-party system simplifies things for the American voter. What could be simpler than two choices? In actuality, the system encourages politicians with a wide range of policies to pack themselves uncomfortably into one of two parties. In countries with parliamentary governments, party label can be a useful shorthand for policy platform. Less so in America, where politicians more commonly vote with the opposing party on key issues.

This broad obfuscation of policy leads not to the best politicians, but rather the representatives who stand out amidst the chaos with romantic backstories and charming stage presence on television. The differences between President Obama and President Trump are many, but both can be described as cults of personality in their own right. The President is elected not just to execute the will of the people, but to embody the national spirit. Celebritydom and the aura of it has been winning Presidential campaigns since JFK. Our politicians must have starpower — by design.

Big umbrella parties make for uncomfortable bedfellows. The real political battles often play out in primary elections — such as the recent nomination of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez — that are more consequential than the general election. As such, the well-informed citizen must be plugged in year-round.

There are many candidates vying for your attention in numerous races at your ballot box, but the well-informed citizen must keep tabs on ballot measures as well. California commonly has as many as 18 on any given ballot. Want unbiased information about them? Good luck. As we’ve been reminded in recent weeks, most information you’ll get about these propositions (or the candidates) is by a campaign or special interest group trying to get you to vote one way or the other. You’ll get more straightforward advice on a used car lot.

If American Democracy was a website.

Elections are not-so-conveniently sprinkled throughout the calendar. On top of national elections in November the well-informed voter needs to keep tabs on local and special elections that could occur at any time. Only 17 of the 50 states provide same-day voter registration, so if you’re not registered chances are you’ll need to handle that before you can vote. Every state has a different process for voter registration and voting.

Once the election is over, the well-informed citizen should follow the actions of congress to keep their representative accountable. The 114th congress introduced over 12,000 bills over the course of their two years in office, and the average length of bills has increased by over 600% since 1948. Their language, of course, is unintelligible to anyone without an advanced law degree.

We have reached a scale, volume, and pace in American politics that far surpasses our cognitive ability as a species to process without well-designed interfaces. The existing interface between the towering machinery of government and the people does the commonwealth few favors in managing that deluge of information.

To Signal From Noise

In January of 2018, amidst rising tensions with North Korea, residents of Hawaii awoke to an incoming ballistic missile warning that concluded, “This is not a drill.” For a full 38 minutes, 1.4 million people believed their lives would soon be over. They called loved ones to say goodbye. Some hid in storm drains.

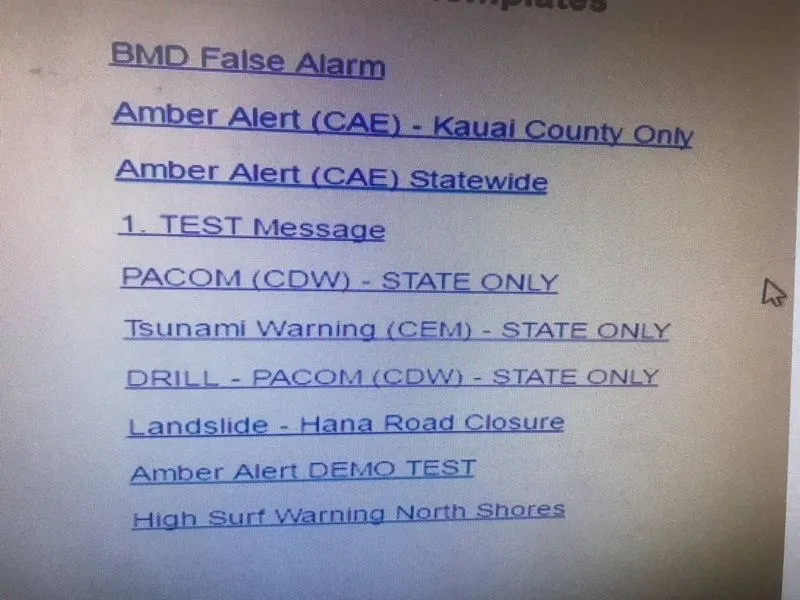

Hawaii’s emergency alert system, featuring both the real and test ballistic missile alert options.

It turned out to be a false alarm. The culprit? Poor interface design in the state emergency alert systems, which made the real alert nearly indistinguishable from the intended test alert. A high risk system ignited pandemonium across an entire state because of a user interface that didn’t take care to distinguish a humdrum drill from the signal of impending apocalypse. The information was obscured, the user wasn’t paying complete attention, and chaos resulted. Sound familiar?

Design is often the challenge of organizing complexity into clarity. The human mind is powerful, but its ability to process information has clear limitations. Our capacity for processing large amounts of information is directly dependent on the organization of that information.

With patience and concentration, you can probably read the poem on the left, but it contains no more information than the neatly organized and punctuated version on the right.

Spring and Fall (1880) by Gerard Manley Hopkins, written using continuous script (left)

We do not live in a time short on well-designed interfaces for navigating complexity. Indeed, mission statements like “Organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” have produced the world’s most successful companies.

Democracy is messy, but does it have to be this messy? What would it look like for American democracy to have a well-designed interface? What would happen if the chaos of information about candidates, platforms, and bills were clear, simple, explorable, expandable, and comparable? It surely wouldn’t solve all our problems, but it could provide clarity for the many people alienated by the avalanche of biased and obscured information about our political process, policy, and those we elect to serve our common interest.

Design for America

Fortunately, some have seen this challenge to democracy and produced new interfaces for exploring election information. Perhaps the most ambitious is BallotReady, a nonpartisan and personalized guide to your ballot. BallotReady focuses its efforts on the local races and ballot initiatives for which clear, reliable information is the most difficult to find.

The lynchpin of success is trust. BallotReady’s team of researchers have an open and explicit policy on how they collect information from endorsers, boards of elections, and directly from candidates. All information is linked back to its original source for transparency. Issue stances are not taken from third-party news articles, and must be “succinct, specific, and actionable” — bypassing platitudes to focus on specific policy support.

The interface is intuitive on both mobile and desktop. The hierarchy of information prioritizes actionable information for voting, with a landing page that highlights the upcoming election date and the voter’s polling place before diving into expandable categories of federal candidates, state candidates, local candidates, judicial candidates, and ballot measures. Within each race voters can easily compare candidate stances on a wide selection of issues.

That information is only useful insofar as voters can recall it at the ballot box, so the interface invites voters to build their personal ballot as they explore and decide. The end product is a simple list voters can refer to in the voting booth.

Of course, an app can only go so far in addressing the need for clear, citizen-friendly experience at the interface of American democracy. My hope is that this is only the beginning for the interfaces we use to engage with government so that we may one day all call ourselves well-informed citizens. We need a fundamental overhaul of the election process. If Thomas Jefferson was right, democracy in the 21st century depends on it.